My Writing Living: Professor Katy Shaw

Katy Shaw tells us how she combines her work as an academic with her own writing and her advocacy work in the cause of creative diversity.

Professor Katy Shaw of Northumbria University in Newcastle upon Tyne is an expert in 21st century literature, with research interests that include working-class literature, cultural representations of post-industrial regeneration, and the languages of comedy. She is the author of several books, including most recently Hauntology, which explores the persistent role of the past in the present of contemporary English Literature.

So far, so academic. But her interests and preoccupations with diversity in writing – particularly when it comes to region and class – have made her university job a strikingly outward-facing one too, far from the ivory tower stereotypes of old.

Katy returned to work in her native North-East a couple of years ago, having previously worked at several other universities including Greenwich, Brighton and Leeds. “I grew up in Newcastle, surrounded by books. My mum was a nurse, and my dad worked in the shipyards but was made redundant three times before I was three years old. So, he went to university and re-trained as a teacher. Consequently, my childhood was filled with my Dad studying, so I was read to a lot as a child and absolutely loved books.” It was while studying English as an undergraduate at Cambridge University that Katy’s interest, both in education and in contemporary literature, was sparked: “I loved the idea of writing as this live, reactive, responsive tool,” she tells me.

I loved the idea of writing as this live, reactive, responsive tool

Her subsequent PhD and simultaneous post-compulsory PGCE at Lancaster University also equipped her to view English as a subject that “could fly in different contexts”. And by its very nature, Katy’s specialism in 21st century literature means that her area of interest is a dynamic and constantly changing one. “It’s the idea of literature as a process. The lovely certainty about being a Shakespearean scholar, or a Victorian scholar, is that the material you’re studying is done; it’s finished. Whereas the challenge of the contemporary is that it’s incoming, it’s evolving as we study it. I say to my students: the scary but also the exciting thing is that we are part of the critical conversation that will form this period of literary history and criticism.”

Katy’s own writing frequently has to take a back seat to her other responsibilities. “I’d love to do more writing! But it’s a massive juggle what with my teaching, my research, and the admin. I also have leadership roles which are another pressure on my time. I currently have a quite broad portfolio: I’m Deputy Head of the whole Department of Humanities and I’m also in charge of cultural partnerships. Just as for most writers who don’t write full-time and have another job, writing for me is about grabbing time when I can. I write a lot of journalism as well and that’s lovely because then I have a deadline to write to. Without that deadline, I find it difficult. But then again, I think it’s important that I’m honest with my students, because it’s this type of career model of portfolio working that they themselves will experience in future. There’s no point in telling them that writers live these romantic lives of just sitting down and pondering because then you’re not preparing them for real life, which is overwhelmingly about quick responses and quick turnarounds.”

I think it’s important for students to see that I’m not just an academic; that we are all part of a wider community of writers

Katy’s partnership and outreach work means that she is also now much in demand to speak at events and do media interviews, although she turns down most requests. “I’m very aware that some academics make quite a living out of doing TV and festivals and so on. I only say yes when it’s a project that I really believe in and where I think I can make a difference, and not just within my subject specialism of English. I’ve been part of a couple of big national campaigns on female mentoring – women in leadership is something I’m passionate about. It’s also great to appear at book festivals – last August I did an event with Nicola Sturgeon at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on the subject of writing in Scotland and the north of England. These kinds of events are really exciting because you can see the potential for real change just by getting the right kind of people in the room together. And I think it’s important for students to see that I’m not just an academic; that we are all part of a wider community of writers.”

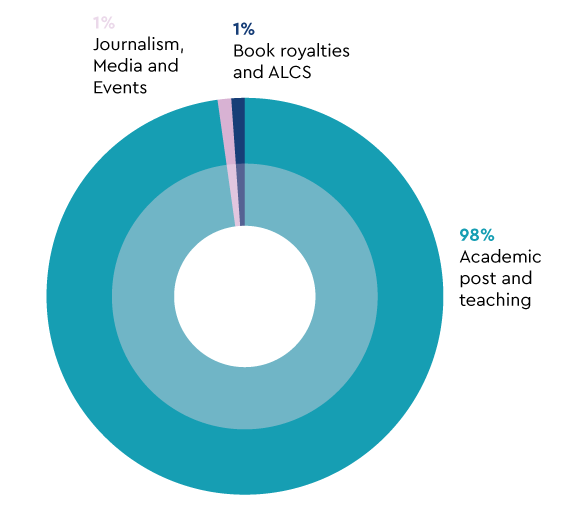

The vast majority of Katy’s income comes from her full-time university post; she earns very little in book royalties. “In terms of academic book sales, I make next to nothing – I might get a £10 royalty cheque once a year if I’m lucky – and then from ALCS, the highest payment I’ve ever had was £80.” When it comes to her additional projects, whether it be her journalism, media appearances, advocacy work and speaking engagements at events in conferences, much of this is undertaken for payment in kind rather than money.

Katy’s average income sources:

With the question of whether writers should ever work for free – a regular preoccupation at ALCS – it’s important to stress that Katy never works for nothing. “I don’t do things for ‘free’ because that just de-professionalises this whole way of working and sets a bad precedent. I might do an event in exchange for tickets so my students can participate; or in terms of partnerships, if an organisation will come in on a project where we can enable something together.”

More recently, Katy has been working with ALCS and the All Party Writers Group (APWG), participating in lobbying work for changes in government policy and practice in the publishing industry around creative diversity and social class. “One of my areas of research is working-class writing, and I’m academic lead for our university partnerships, one of which is with New Writing North, the biggest writing development agency in the UK. One of the things we’ve been looking at is how engaging working-class writers in a writing development programme could potentially act as a strategic intervention, leveraging quite big results for writers, and also for the publishing industry. We published a policy report on the back of the project on 1 May this year – International Workers’ Day – and we’ll be presenting this to parliamentary groups once they’re sitting again.”

“There are also some very exciting developments going on up here at the university around publishing, which many of our regional publishers are going to be part of. So it all feels like a bit of sea change.”

Interview by Caroline Sanderson