My Writing Living with Steve Stamp

Steve Stamp is a BAFTA award winning comedy writer and actor, known for creating and writing the BBC sitcom People Just Do Nothing, the Channel 4 crime drama The Curse and most recently the BBC sitcom Peacock. We spoke with him to discuss his formative creative pursuits, his approach to comedy writing and the evolution of his writing process.

Did you have any creative pursuits before People Just Do Nothing?

I’ve always wanted to create things. When I was a kid, I quietly drew cartoons, wrote little stories, stuff like that. I suppose it was attention seeking, in a way. As I got older my confidence grew (as did my need for attention) and I started posting stupid poems and short scripts on a blog. I think when you are bold enough to start putting your ideas out into the world, you start attracting other creative people. I wrote a short story that my animator friend Tim McCourt read and really liked. He asked if I’d be up for letting him and his mates animate it, which was very flattering, and we ended up making a little animated short called Drawing Inspiration.

Moments like that can really change your life. I think that’s why surrounding yourself with creative people is so important. A similar thing happened with my first experience of directing. I had a mate who worked in production, directing music videos and we ended up collaborating on a music video together. These early experiences of creating something from scratch felt very rewarding, especially because I was working with such talented people. At that time, it was an escape from the office job, but more than that, it was me actively pointing myself towards the things that I wanted to be doing.

The show started as a web series on YouTube. What was the writing process like in these early days?

Initially, we didn’t want to plan much at all, but after the first couple of videos we realised it was quite nice for us to at least know the dynamics and what might happen in the scene. For there to be some sort of structure to our ramblings. We started meeting up at the weekend to talk about what should happen in the next videos. I was a bit like a producer at that time, pushing things along, writing stuff down, organising the shoot days. I would write beat sheets so that there was a rough journey and we could have a few pre-prepared jokes or funny moments.

People Just Do Nothing was then picked up by the BBC, how did this change in scale impact your writing process?

Initially we wanted to keep the beat sheet writing style. We didn’t want to lose the raw improvisational style, which we felt was one of the strengths of the show. We were very overconfident. However, when Roughcut (the production company) saw our Word document of bullet points, they were forced to give us a very polite reality check. Ash Atalla had produced The Office. He assured us that although it looked like everyone was just messing around and improvising, it was actually a very tightly scripted show. So, we agreed to script it properly.

I was the only one who really had any interest in writing scripts, so I threw my hat into the ring very enthusiastically and became the lead writer for the show. What followed was a real learning curve, figuring out how to brainstorm the ideas as a group and then turn those into coherent scenes that everyone, including the BBC, was happy with. It was not easy. I read books (Save The Cat!, Into The Woods), I read scripts (The Office, Alan Partridge, Peep Show), I tried to listen to everyone and understand where they were coming from. Eventually we emerged with a pilot script. I’m forever grateful to Roughcut for facilitating my growth as a writer in that way.

How did you find the transition from writing just among yourselves to having to work and compromise with producers?

Every stage was another learning curve. Pre-production for example – we were obviously used to making all the decisions and we had a lot of strong opinions about how the characters would dress, what equipment they would have in the pirate radio station, and we also didn’t want casting to be done without our involvement. The shoot days were also very different. It was obviously exciting but on set everything was suddenly a lot more complicated and the sheer scale of it meant that we were very out of our comfort zone. It was all incredibly intimidating, but we had strength as a group, and we were determined to create something that we were all proud of.

Then there was post-production – we felt like we were being pushed out of the edit and had lost control of our own show. I ended up having to write emotional emails begging for them to listen to us. Over the years, this began to improve. We’ve had to figure out systems so that everyone can feel like they are being heard and notes fed in. Making a TV show is such a collaborative process. We had to eventually come to terms with the fact that we couldn’t be across everything and we couldn’t control everything.

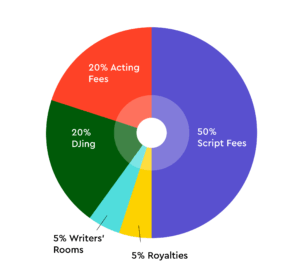

Estimated breakdown of income sources

It’s often difficult earning a living through writing alone, with many authors having to supplement and diversify their income streams. As part of the My Writing Living series of articles, we ask those interviewed to break down how they earn their living.

The Curse felt like quite a shift in terms of tone, genre etc. What made you want to tell that particular story?

We met James De Frond and Tom Davis at the BAFTAs and got on with them straight away. We were very much on the same wavelength comedy-wise, and we talked about wanting to do something new, something completely different from People Just Do Nothing. They had this idea to tell the story of the Brinks Mat robbery, so we had a few meetings and came up with an idea for a show. I think part of the appeal was the fact it was set in the 80s. In terms of wardrobe, music, set design, we knew it could be a really cool show. We all immediately got excited about what sort of facial hair our characters would have and everyone started growing mullets. It felt like an exciting challenge to balance dramatic storytelling with strong comedy characters. We also liked the idea of shooting something in Spain, for obvious reasons.

With your latest show Peacock, you continue to draw humour from insecurity and delusion. Why are these flaws such fertile ground for your comedy?

I think it’s probably because it’s what we struggle with ourselves. You’re also aware that you’re getting older, you’re supposed to be achieving things, getting married, having kids and political opinions. In our writers’ rooms, we will all share stories about how pathetic we are. It can be tiny social interactions or even imaginary fears. Those are the things that I find fascinating about human behavior – anxiety, the way we overthink situations and complicate our lives – it all ends up going into the scripts.

In your work, humour comes more from fully realised characters than punchlines. How important is it to delve into their psychology?

With People Just Do Nothing, we had the characters first and then started building a world around them. I think this made me appreciate the importance of strong, complex characters. They are what makes a show work, ultimately. If you have fully formed characters, you can put them anywhere in the world, in any situation, and you know you’re going to enjoy watching them.

I think being on the acting side has also been very useful because you really feel when a character is underdeveloped or doesn’t contribute enough. As an actor you find yourself literally just standing there not knowing what to do. I find it useful to focus on each character individually at the end of a script pass and giving them all a little bit of individual attention.

Do you think good comedic writing is something that can be studied and learned, or is it more about innate personality traits?

I think you can absolutely study and learn the mechanisms of comedy. Structure and pace are so important. Comedy can be forensically dissected. What matters most though is your perspective. Good writing reveals something about how you see the world, and what you find funny. I don’t think you can fake that. The things that really make people laugh are the moments where you feel like you’ve got an insight into someone’s brain. There’s an honesty and a vulnerability there. It’s almost like an admission of guilt. It has to come from somewhere genuine. For me, the more personal it feels, the funnier it is.