THE ALCS INTERVIEW: GERALDINE McCAUGHREAN

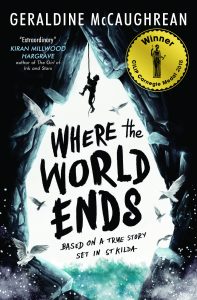

Children’s writer Geraldine McCaughrean recently won her second CILIP Carnegie Medal for Where the World Ends. Set in the St Kilda archipelago off north-west Scotland in the early 18th century and based on a true story, the novel follows a group of boys, marooned on the remote sea stack where they have sailed to hunt the seabirds that sustain their community.

Many congratulations on your second Carnegie Medal. What was the original inspiration for Where the World Ends? How did you come across the true story on which it is based?

Thank you. I knew vaguely about St Kilda and its evacuation in the 1930s, but nothing in detail. I was given a copy of the beautiful Atlas of Remote Islands by Judith Schalansky and it features in it. But then my daughter wrote a play set there and took the chance to go to St Kilda. She came back so smitten with the atmosphere and anecdotes of the place that I caught Kilda fever (a common affliction among the Scots) and pounced on one of the stories she had told me.

What sort of research did you do for the book in order to so successfully take us to a place I understand you haven’t actually visited?

The historical allusion to the marooning of boys on Stac an Armin amounted to two whole sentences. But that suited me fine. The less fact, the more room for fiction. There were no names given, no account made of how the boys survived or what the experience did to them. That left me free-range, pecking up grains of fact to nourish the egg within me, hoping it would hatch out into something living.

Where the World Ends feels as if it’s partly about the things that sustain us through challenging times, especially words and stories and dreams. Was that part of your intention to write about that?

Where the World Ends feels as if it’s partly about the things that sustain us through challenging times, especially words and stories and dreams. Was that part of your intention to write about that?

Oh yes. I’m always banging on about interior worlds and the imagination as an escape route from a burning world. I fear ‘playing in your imagination’ sounds like borderline lunacy to a lot of children these days. But regardless of being a writer, I have always prized my imagination as a place-of-retreat-and-play and I’m appalled at the thought that human evolution might one day remove it, as it did our prehensile tails. I was once doing my schtick to a class and one particular boy beamed at me with total delight throughout. A teacher afterwards said how glad she was I had said it was alright to have an imaginary world, because the boy in question had been bullied mercilessly for letting slip that he did.

There are a few parallels between Where the World Ends and Lord of the Flies – were you conscious of that book when writing?

When I started thinking about the book, I wanted to do a kind of Lord of the Flies turned on its head, in which the boys (being from a highly religious and gentle community) decided to create an ideal society which put the adults to shame. But it just didn’t work. There was no tension, no adversary, no elastic ruching the material. The boys all needed to be different, not cohesive, so I entrusted the story to them and took it wherever they led.

Your novels often feature far-flung settings, is a sense of place crucial when you start plotting a new book?

I do adventure and peril – because that’s what I liked when I was young and because it is also what my life (thankfully) lacks! There are two useful places an author can go if child protagonists are going to be plausibly imperilled: one is the Past, the other is somewhere remote and difficult. I mostly do both. Besides, it’s a great way of going, in my imagination, somewhere I’m never actually going to go.

What do you always hope readers will take away from your books? For example you say you’re keen to challenge young readers linguistically?

I hope that, at some subliminal level, they will enjoy the rise and fall of the sentences, though it’s not important. I’m not wilfully trying to be edifying or anything: it’s just that some people get pleasure from style as well as plot. I chiefly want them to be transported to somewhere that feels real and to meet a bunch of people who, for the duration of the book, feel like new acquaintances that they mind about. Increasingly – I suppose age induces it – I like to include adults whom the reader can sympathise with and mind about. When I was reading as a child, I did not want to read about children more than about adults. After all, all children have been a child but they’ve not yet had the chance to be an adult.

Who were the writers you admired when you were growing up?

My brother first and foremost (he got published when he was 14); Elyne Mitchell and Marguerite Henry (I was horse mad); Rosemary Sutcliffe (I always assumed, as I did with all authors, that she was dead, whereas, in fact, my future editor was busy editing her books at the time); Mervyn Peake – Mr Pye was the first time I remember thinking, “I wish I’d had that idea first”.

ALCS recently published new research into author earnings’ which shows a continuing decline in incomes. Have you found it harder to earn a living over the years, despite being so prolific and earning growing recognition for your work?

I have been very lucky. I’ve written a LOT of books so although advances don’t go up much, percentages tend to be smaller, books are quicker to go out of print and people don’t need to pay more than a penny for most of mine, somehow the backlist along with at least one new book a year, goes on bringing in a living wage.

What bewilders me more than anything else, given the erosion of authors’ earnings in relation to publishers’ earnings, is why the practice continues of paying six-figure sums to first-time authors – and I don’t mean celebs. My editor said that, in his experience, an author’s first book was rarely their best; their fifth or sixth book was. Do the public really rush out and buy a book because they’ve read that the author was paid half a million? Established authors being paid a fraction of that for their latest book must look on with incomprehension at this search-for-the-next-best-thing consuming their publishers’ profits. Besides which, most ingenue authors would take ten quid, just to get published! I know I would have at 20.

In your Carnegie acceptance speech you spoke out against the dumbing down of children’s literature – what moved you to make this the focus of your speech?

Anne Fine told me once – if you’re going to make a speech, for goodness’ sake make it about something. So I did. But the ultimate drift of my argument (which rather got lost in the wash) was how good it was to see that Carnegie-type books were still finding a place in the world despite a seeming trend towards the simplification of language. I like words. The older I get the more I realise that if I like something, lots of other people do, too. Even children. So give ‘em words – lots of them – at the age when they are best equipped to absorb them – especially since words will enable them to think, reason, argue their corner, create, express themselves, form opinions rather than having to think-with-the-herd, enjoy literature, and hold their own in the world. Why deliberately simplify their vocabulary when the lack of one is such a handicap?

It’s quite some achievement to win a second Carnegie Medal 30 years on from your first, not to mention the fact that you are also, along with Anne Fine, the Carnegie’s most shortlisted author! What does this second win mean to you?

Unalloyed delight. I’m ashamed at how much I wanted to win it again – just to prove that it wasn’t a fluke the first time and that my career hasn’t been a downhill cruise ever since. The first time felt like permission to call myself an author. This time it felt like permission to go on calling myself an author. Part of me still feels like a fraud – as if every book accepted has been a lucky fluke, but it’s too late to ‘fess up now: that I’ve just been enjoying myself all along, doing what I’d be doing in my spare time if I had a proper job. I’m just glad no one has seen through me… There are a lot of extremely clever authors out there whom I would account professionals to my amateur.

Interview by Caroline Sanderson: author, freelance books journalist and editor of ALCS News. She also chairs events at book festivals and in bookshops throughout the year.

Photograph © Katariina Jarvinen